Study of northern Michigan lakes’ muskie seeks clarity on Great Lakes strain

Muskie tagged in Elk Lake and Lake Skegemog spawned in the Torch River, a high-traffic, developed channel. (Marada via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

Muskie tagged in Elk Lake and Lake Skegemog spawned in the Torch River, a high-traffic, developed channel. (Marada via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)In September 2009, Kyle Anderson hauled a 50-pound Great Lakes strain muskie from the turquoise waters of Torch Lake in northern Michigan. While the fish was big enough earn a spot in the state record books, it was already listed in data logs of Jim Diana, a professor of fisheries and aquaculture at the University of Michigan.

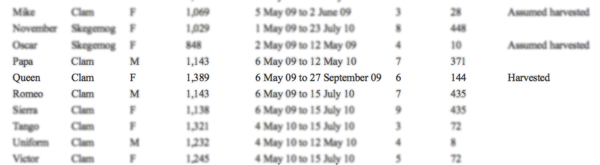

In Diana’s records, the muskie was known as Queen, a 1,389-millimeter female tagged with an acoustic transmitter on May 6, 2009. Queen, named so as the 17th of 24 fish tagged and assigned a letter of the phonetic alphabet, was part of a study of how this muskie strain moves and spawns throughout some of the state’s premier fishing lakes.

The results of the study could help the state better manage the species throughout Michigan, where it hasn’t inspired the same fervor as in muskie-crazy Wisconsin and Minnesota.

“Michigan has been funny about muskies,” Diana said. “If you go to Wisconsin or Minnesota, that’s it. Fisheries management is muskie management, and they have hatcheries all over the state, and everybody’s buying cabins to go muskie fishing.”

“It’s a huge tourism thing, and Michigan is really kind of ignoring that resource, I think,” he said.

Self-sustaining muskie populations in inland lakes are on the decline, likely as a result of problems with reproduction. This study sought to learn more about the spawning habits of the Great Lakes strain of muskie, which differs from the Northern strain common to Minnesota and Wisconsin’s inland lakes.

Methods

The researchers netted and tagged fish from a naturally reproducing population in a chain of lakes in Antrim county, a string of connecting waterbodies that includes Torch Lake, Elk Lake and Lake Skegemog. There are relatively few muskies in those lakes: Whereas a single net in a previous Green Bay study would bring in five or six muskies, Diana said, this system would give up just one muskie across five or six nets.

But muskies that do survive there can get big. The 50-pound Queen lost its spot as the species’ state record in 2012 to a 58-pound fish caught in Lake Bellaire, which is just upstream from Torch.

In the spring months of 2009 and 2010, the researchers sought out spawning muskies in the nighttime hours using a tag-detecting hydrophone and a 1,000,000 candlepower spotlight. They logged the habitat, size and GPS locations of groups of two or three fish slowly swimming parallel to each other, which suggests spawning is imminent. After the spawning seasons, the researchers used the hydrophone in biweekly surveys to chase down fish and log their positions.

Queen’s entry in the study, which is published in the journal Environmental Biology of Fishes (Credit: Diana et al/ Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014)

Results

The researchers were surprised to find that most fish tagged in Elk Lake and Lake Skegemog swam upstream to spawn in the Torch River, a heavily modified channel that connects Skegemog to Torch Lake. It’s surprising because declines in muskie reproduction have been linked to shoreline development, yet the fish preferred the dock- and cabin-lined Torch River to the the seemingly prime spawning habitat in Skegemog, which has plenty of woody debris.

The boat traffic and development along one of the system’s prime muskie spawning spots may be one clue as to why there are so few muskie here, Diana said.

“I think there’s so much disruption of muskies in there that spawning is probably less successful,” he said.

The study is an early step in learning more about the inland behavior of the Great Lakes strain of muskie, which is thought to be the strain native to Michigan and now exclusively stocked by the state over the Northern strain. More clarity in understanding which spawning habitats deserve protection will be needed if the state wants to raise the profile of the species to the levels found in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

“It generates a lot of economy in those states, and we could do better and maybe we should be,” Diana said. “We have some great muskie fishing beyond just Lake St. Clair, which is probably the best muskie fishing in the world.”

Muskie attempting to jump over Wingra Dam (Richard Hurd via Flickr CC BY 2.0)

0 comments