One fish, two fish: Underwater video works for fish population counts

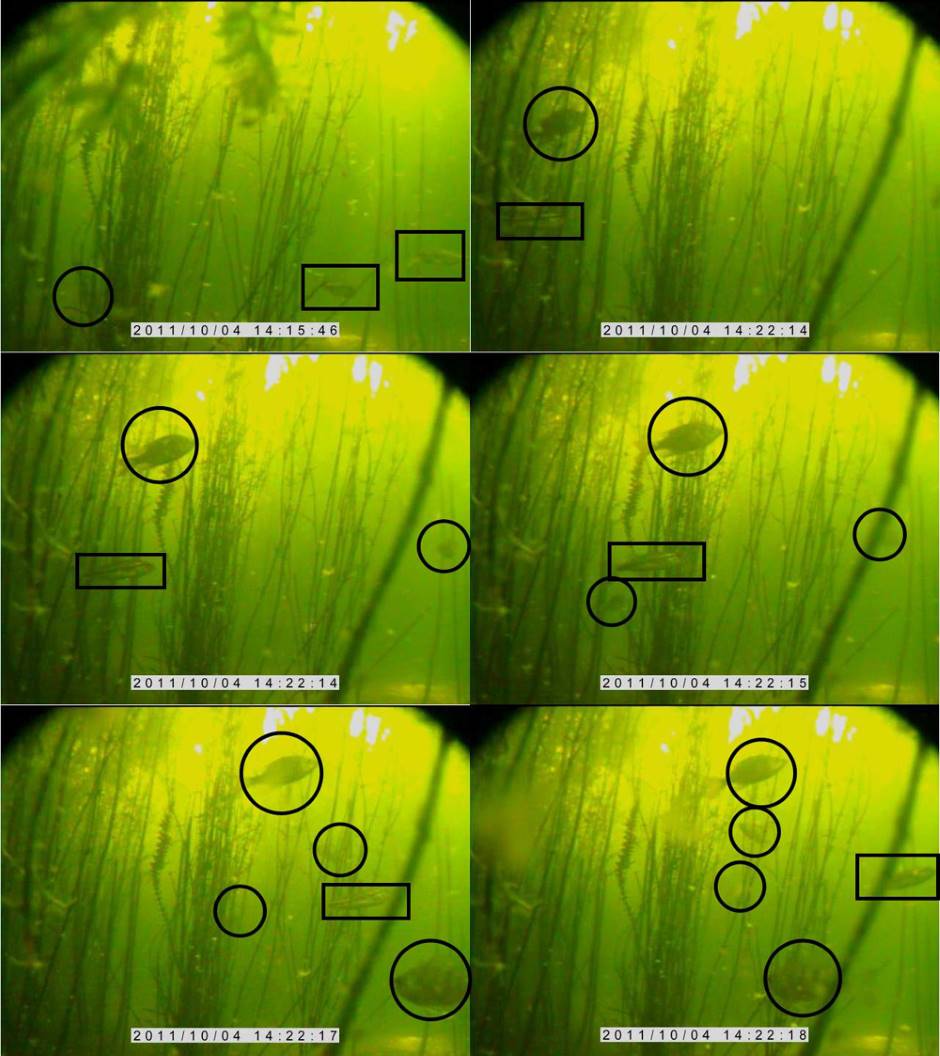

The underwater video helped spot panfish amongst the hydrilla. (Credit: Kyle Wilson)

The underwater video helped spot panfish amongst the hydrilla. (Credit: Kyle Wilson)For those in the business of fishery management and conservation, numbers count. But fish aren’t keen on filling out census forms, and even small ponds can house thousands of individuals among dozens of species. Assessing those populations is no easy task, but a study from the University of Florida shows that underwater video can accurately enumerate the relative abundance of fish, even in obscured environments.

“Before the use of underwater video, you’d be trying to net fish or use a hook and line, neither of which are very efficient methods of sampling,” said Kyle Wilson, lead author of the study.

Part of a larger project that examined Hydrilla, a genus of invasive aquatic plants that have spread from southeast Asia to the U.S., the study addressed the challenge of sampling fish populations in ponds fraught with the pervasive waterweed. In those ponds, Hydrilla grows so thick that it forms a canopy, making it near-impossible to cast a line or net with any success.

Wilson and the other researchers considered two alternative sampling methods: divers, who could observe and tally fish the old-fashioned way, and waterproof cameras capable of capturing underwater scenes in digital video.

The divers, Wilson said, were quickly vetoed.

“A snorkeler is just as likely to get snagged as any other instrument,” Wilson explained. “In the best situation they get a good view, but they still have to write everything down.”

So the team opted for the camera. Small, lightweight and with nothing to catch on besides a cable, it seemed a suitable means to peer through the submerged thicket. An Australian research group had proven the usefulness of video sampling in the Great Barrier Reef’s crystalline waters, but whether the technique would work in a murky Florida pond remained to be seen.

Methods

Over 13 weeks in 2011 and 2012, the researchers studied three experimental ponds that, when necessary, could be “drained like a bathtub,” Wilson said. This would allow the researchers to verify their population estimates at the study’s conclusion.

Each day, Wilson took a jon boat to one of the ponds and started at a random side. He paddled out until he came across a particularly dense patch of Hydrilla — often thick enough to hold his boat in place without using an anchor — then tossed the camera into the water five or six feet deep. After recording to an onboard DVR for about 10 minutes and measuring dissolved oxygen with a YSI probe, Wilson hauled the camera in and repeated the process 19 times more.

Although the sampling went relatively smoothly, Wilson said the thick plant cover caused its share of nuisance.

“It’s like trying to parachute through the rainforest: You’re not necessarily going to reach the bottom,” Wilson said. He recalled one attempt to improve the camera’s performance:

“We tried making a camera that would pierce the canopy like a broadhead arrow,” Wilson said, laughing. “That didn’t work.”

Results

With the sampling complete, the team analyzed each recording in 30-second intervals, counting the maximum number of individuals on screen at any one time during that interval. Then they compared those figures to the known population counts of each pond. The results showed a strong positive correlation between the on-camera counts and the actual population, indicating that underwater video can indeed be used to determine proportionately accurate population densities.

While the proven success of video sampling could simplify fishery researchers’ jobs, Wilson cautioned that the method is less likely to produce meaningful results in the wild, or other settings where long-term population counts and behavioral patterns can be hard to establish.

“If you don’t know how many fish are there, if you don’t know how they’re using the habitat, then how can you make a recommendation to the fishery managers that maintain it?” Wilson said.

Wilson, now a doctoral student at the University of Calgary, will only serve as an adviser on any continuing research, which would test the video sampling method in larger lakes. He sees video sampling as an opportunity to build productive relationships with the tech-savvy anglers who especially stand to benefit from well-kept fisheries.

“Maybe we could bridge a gap between researchers and the anglers who are using this technology already,” Wilson suggested. “We have limited staff, limited funds, so we can’t do all this ourselves.”

0 comments