Fish Gill Antibodies Keep Fish From Getting Sick

It’s kind of strange how fish can swim around with gills open directly to the water and not immediately get sick from all the waterborne pathogens swimming around them. It’s weird, but also pretty amazing.

Scientists at Penn State University’s School of Veterinary Medicine have been intrigued by the ways that fish gills help to protect the organisms from disease for some time. And though they had a few guesses as to how gills do it, they didn’t really know for sure.

To eliminate that uncertainty, researchers at the university set out to investigate, testing one of their more likely hypotheses. That specific antibodies produced by fish are helping to protect them from waterborne illnesses to keep them healthy.

In previous studies, the researchers had identified a specific antibody immunoglobulin, called IgT, that looked to be the primary antibody involved with how fish respond to pathogens that attack their skins or guts. They also found that IgT coats bacteria living in those areas, likely helping to partially immobilize the microbes and keep them from expanding out of control.

In this work, the scientists were interested in the immune responses that originate in gills when fish are exposed to pathogens. The difference between skin and guts and gills is that gills are respiratory organs considered mucosal surfaces and so it wasn’t a given that they would respond the same way.

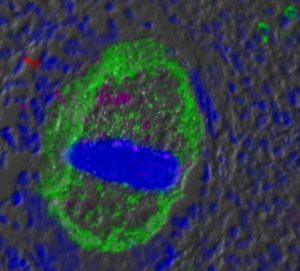

A parasite in a trout gill is coated with the IgT antibody, labeled green. (Credit: Penn State University)

To investigate, the researchers first examined the gill mucus of rainbow trout and found that IgT was abundant, though other immunoglobulins, IgD and IgM, were also present. Examining the gill microbiota, they found that IgT was the primary antibody coating bacteria in the gills, which was consistent with the team’s earlier findings in fish skins and guts. To see if this prevalence indicated a role for IgT in responding to pathogens in the gills, the researchers exposed the rainbow trout to a parasite that causes white spot disease, a pretty common infection in farmed, pet and wild fish that targets the skin and gills of fish.

A few weeks after the infection, the team surveyed the parasites that were left in the gills and found them overwhelmingly coated with IgT. Only a few had some IgM coating them and no IgD-coated parasites could be detected. The fish that survived the infection also had a significant increase in IgT-producing B cells in their gills, which is an additional sign that the IgT response is a key to fighting the parasite.

To reaffirm the results, the Penn State team conducted a similar experiment with a different bacterium that affects fish gills and skin. That experiment showed that increases in the cells that produce IgT and IgT itself were specific to the gills and not linked to some other part of the fishes’ systems. Those results are the first time that a non-mammal species has been found to locally induce such a mucosal immune response.

Researchers say that their findings reveal that sophisticated immune defense mechanisms in respiratory surfaces, like gills, must have come about very early in vertebrate evolution. There is an ancient partnership between mucosal immunoglobulins and respiratory surfaces in fish, they say, which shows that the basic principles controlling respiratory surfaces, from an immunological perspective, are found in all jawed vertebrates.

On a more practical level, the results can inform strategies to design better, cheaper vaccines for fish, which is crucial for making fish a safe and affordable source of food for the world. Some of these vaccines are bath vaccines, which are dropped in the water and absorbed through fish gills and skin. And so knowledge of the mechanisms controlling gill function and immune response may help future researchers find ways to deliver vaccines through gills and give them immunity to infectious diseases.

The study was partly funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health and the European Commission. Full results are published online in the journal Nature Communications.

0 comments