Ecosystem Service Map Directs Anglers to Mountains Streams

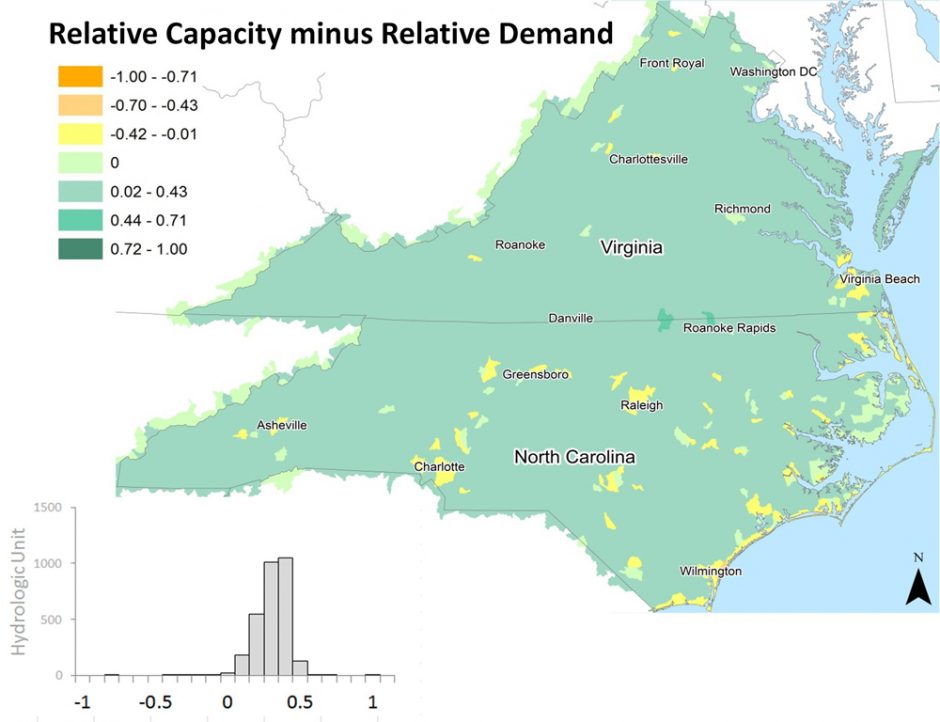

An example of cultural ecosystem services mapping, with green areas showing where a fishery's capacity outweighs demand (Credit: Virginia Tech)

Productive fishing spots are often supported with anecdotal information from anglers or naturalists spending time near the water. While these reports may work well enough between fishermen, resource managers and biologists typically prefer more concrete data to make decisions. This sentiment does not discredit the vital exchange of information between anglers nor their contributions to creel surveys—instead, it calls for the inclusion of more observable metrics.

Considering Anglers in Ecosystem Service Maps

In 2014, researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey and Virginia Tech conducted a regional study to map the quality, capacity and demand of freshwater fishing sites in various environments. Virginia and North Carolina serve as good examples due to the states’ unique geographic makeup. The point of the map is to provide a definitive answer on where the best opportunities for fishing are.

“We chose fishing because it was popular and we knew that there were data available,” said Paul Angermeier, USGS scientist and Virginia Tech professor. “We found that we had some reasonable data—not the perfect data, but we thought that we could tell an interesting story.”

Fishing means so much more than the occasional angler reeling in an exceptionally large catch—fishing is connected to cultures, spirituality, recreational activity, the global economy and a valuable food source. Recognizing these important roots, resource managers everywhere consider population distribution to be important, and it just so happens that anglers also value that data.

“We’re not just crazy about fishing… Well, some of us are,” Angermeier said. “But there’s a larger social and management context in which fishing is a really important activity.”

Keeping anglers happy is an important part of fishery management, particularly as fishing permits, angler donations, volunteer work and other contributions are crucial resources to keeping fisheries running.

Angermeier collaborated with researchers Beatriz Mogollon and Amy Villamagna—both of whom Angermeier said “did the lion’s share of the work”—to analyze fishing sites. The group focused primarily on key environmental factors that impact recreational anglers and resource managers like habitat quality, fish abundance, boating access and game fish stocking, among others.

Conclusion

Perhaps unsurprising, the research revealed that fishing site quality decreased as waterways flowed from the mountains to the sea. Mountain streams are remote and, while they have slowly been degrading over the years, are still more pristine than most lowland waters. Due to the improved water quality, a greater variety of fish species can be found in the mountains, where they aren’t subjected to pollution and overfishing.

According to Angermeier, gathering data and establishing conceptual models proved to be time-consuming and taxing on account of the numerous articles surrounding ecosystem service research.

“For those who aren’t familiar with the ecosystem service literature… it’s not very standardized in method and terminology,” Angermeier explains. As a result, he struggled to pull out useful information that would help in creating a comprehensive ecosystem service map.

While the focus of this specific study was fishing, Angermeier hopes the study’s analytical approach will be applied to other cultural services that have been historically neglected in terms of research—activities like paddling, bird watching and hiking are culturally significant to surrounding communities but often a forgotten consideration. Providing tangible evidence to support conservation and restoration efforts helps guide ecosystem managers to make data-driven decisions.

With better management strategies, users of the waterways, both the diverse life that rely on aquatic systems for habitat and local communities who utilize the resource, will benefit. “The output of developing this framework is that you can begin to look at management choices in a logical context,” Angermeier said. “You can begin to assess things like the capacity of a system to provide a service, and the demand for that service, and the pressures that diminish that service.”

While Angermeir is hopeful that other agencies adopt his team’s approach to cultural service data mapping, he also has a broader goal of defending fishing as a pastime. He explains, “We hope that [the research] kind of turns a light on for people to recognize that you can view fishing in a different way.”

0 comments