Declining Mountain Streams Still Supporting Fish

Rainbow trout. (Credit: Ryan Hagerty / USFWS Public Domain)

Rainbow trout. (Credit: Ryan Hagerty / USFWS Public Domain)For years, water monitoring programs have documented declines in the water quality of mountain streams as a result of climate change and various forms of pollution that contaminate and deteriorate the waterways. Mountain streams were long thought to be pristine, with clear flowing waters and lower pollution rates than lower altitude bodies. Unfortunately, research has found that these streams are no longer as clean as previously thought.

What is Contaminating Mountain Streams?

A 2021 study published in BioScience assessed data collected over four decades, which revealed that the quality of mountain streams is steadily declining as a result of sediment from unpaved roads and agricultural runoff. While the 2021 study made further conclusions about the causes of the declines, researchers have been noting the changes for far longer—so fish scientists and water quality experts alike have long worried about how these changes will impact biodiversity.

Following these earlier reports, scientists warned of the potential of massive extinctions as a result of climate change and overall declines in water quality. However, a 2016 study led by the U.S. Forest Service found that fish were doing relatively okay, despite the changes. The salmon and trout who typically reside in these mountain streams saw some temperature changes, but not enough to cause an extinction event like the one predicted.

How are Declines in Mountain Stream Water Quality Impacting the Fish?

As outlined by the 2021 study, there are more than just temperature changes to worry about in terms of habitat suitability, and the 2016 study cautions that the declines are still negatively impacting the region. However, the study did help solve a longstanding mystery that has puzzled scientists for years: Why, with all the projected declines, have fish living in mountain streams been able to carry on without much incident?

“Predictions of widespread species losses, however, have yet to be fulfilled despite decades of climate change, suggesting that trends are much weaker than anticipated and may be too subtle for detection given the widespread use of sparse water temperature datasets or imprecise surrogates like elevation and air temperature,” scientists write in the study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

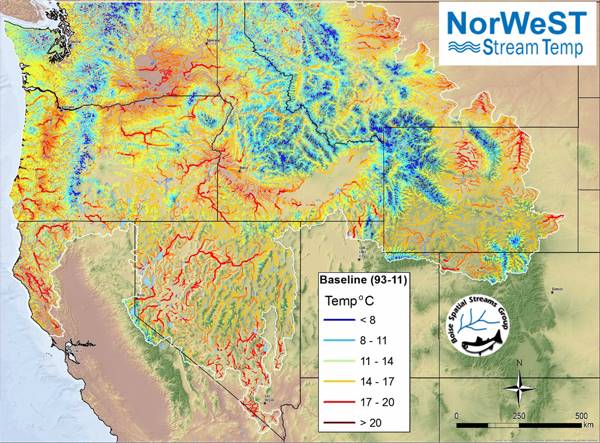

Northwest United States temperature and climate map developed from data at more than 16,000 sites that was used to highlight climate refugia for mountain stream species. (Credit: Dan Isaak / U.S. Forest Service)

In order to get answers finally, scientists used existing data records to analyze stream temperature measurements from more than 100 agencies and a regional climate model built by the U.S. Geological Survey to assess warming trends in 138,000 miles of streams in the U.S. Northwest. States covered in the effort included Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and western Montana, as well as small portions of western Wyoming, northern Nevada, northern Utah and northern California.

The scientists found that stream temperatures have warmed at an average rate of 0.10 degrees Celsius (0.18 degrees Fahrenheit) per decade over the last 40 years. This translates to thermal habitats shifting upstream at a rate of only 300 to 500 meters (0.18 to 0.31 miles) per decade in headwater mountain streams where many sensitive cold-water species currently live. Simply put, pollution and climate change warming these streams are impacting fish habitats, but the changes are occurring much slower than previous studies had proposed.

Conclusion

Fortunately, this means that many populations of cold-water species will continue to persist in this century. However, it also means that mountain communities and the surrounding environment will play an increasingly important role in protecting these habitats as they change over time. If declines continue, it is only a matter of time before there are losses. Still, the results of the study give resource managers more time to complete extensive biological surveys of ecological communities in mountain streams as well as curate conservation planning strategies that can adequately address all species.

The findings of the work build on others made in the Cold-Water Climate Shield effort, and the results were largely unexpected, as scientists note that the cold headwater streams that were believed to be most vulnerable to climate change actually appear to be some of the least vulnerable. And the fact that they were gleaned using existing data is likewise surprising because the measurements had been there all along.

0 comments