Sea Lice and Salmon

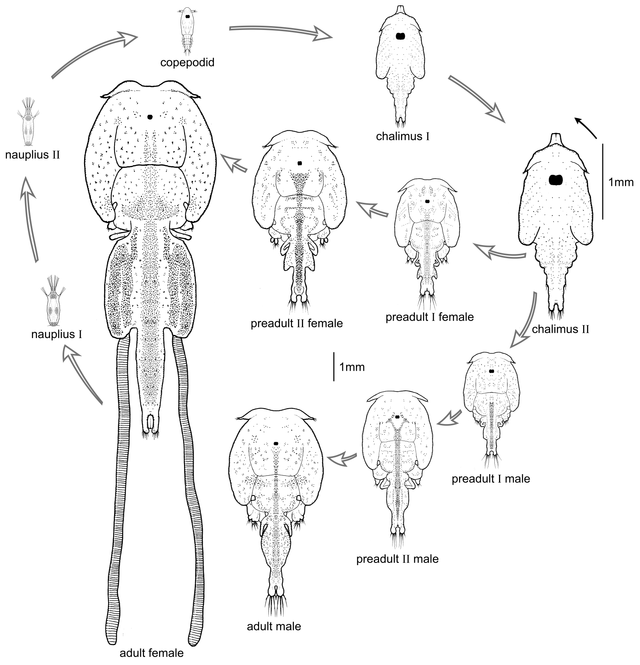

This file contains the visual depiction of the eight life stages of the life cycle (LC) of Lepeophtheirus salmonis (LSa), the salmon louse. Male and female salmon lice cannot be distinguished by the naked eye in the Nauplius, Copepodid and Chalimus stages. First in the larger (note the different scale!) pre-adult and adult stages, sex determination by visual inspection is possible. (Credit: Sea Lice Research Centre (Credit: University of Bergen, Public Domain via Wikimedia).

This file contains the visual depiction of the eight life stages of the life cycle (LC) of Lepeophtheirus salmonis (LSa), the salmon louse. Male and female salmon lice cannot be distinguished by the naked eye in the Nauplius, Copepodid and Chalimus stages. First in the larger (note the different scale!) pre-adult and adult stages, sex determination by visual inspection is possible. (Credit: Sea Lice Research Centre (Credit: University of Bergen, Public Domain via Wikimedia).Much like head lice can work their way through schools of people, sea lice are a common parasite found in fish farms that spreads amongst schools of fish. Sea lice are like many other aquatic parasites that attach themselves to the host and then feed relentlessly, causing a multitude of health issues for fish and aquaculturists.

Aquaculture managers have attempted to solve the issue of sea lice infestations by introducing smaller fish to clean the farmed fish. For example, a salmon farm may use fish such as cunner or lumpfish to regulate sea louse populations. The smaller fish eat sea lice off of the salmon, allowing for the larger species to be protected.

Using other fish to keep prized fish clean of lice allows fishery managers to avoid using chemicals to treat water. While sea lice are not typically fatal, they can make fish sick, and if too many of the parasites attach, the fish is unlikely to survive.

What are Sea Lice

Sea lice are small crustaceans that attach themselves to a host fish, preferring the head, back and perianal areas to feed on their mucus, blood, and skin. Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game states that the crustaceans, also called copepods, are “incredibly abundant – they constitute the largest source of protein in the world’s oceans in their early larval stages.”

There are two species of sea lice, Caligus elongates and Lepeophtheirus salmonis. While C. elongates can be found on a variety of fish, L. salmonis are only found on salmon and other related species. Fortunately, sea lice typically only attach to adult salmon during their time in the ocean and fall off when the fish return to freshwater.

Sea lice live in salt water environments and cannot live for very long in freshwater environments, making salmon a unique target for the species. Salmon spend part of their life in freshwater and the other part in salt water. Salmon generally swim through lice breeding grounds on their way from river to sea or vice-versa.

Sea Lice in Farmed Salmon

While natural circumstances typically protect juvenile salmon from interacting with sea lice, fish farm conditions are very different. Adult and juvenile salmon are reared near each other, only separated by static mesh. While adult salmon are typically unaffected by lice, juvenile salmon are more likely to suffer fatal complications.

Even further, wild salmon close to fish farms are more likely to suffer sea lice infections due to the ideal louse breeding conditions created on fish farms. The ADFG reports, “Wild salmon close to fish farms are 73 times more likely to suffer lethal infections than juveniles not adjacent to fish farms.”

Sea lice can survive for about three weeks off their host—making the transfer from farmed to wild salmon possible and putting native, wild salmon at risk. The ADFG states, “A fish farm can also elevate the rate of sea lice infestation in salmon up to 40 miles from their pens.”

In short, sea lice can quickly spread from fish to fish both within and outside of farm environments. Fortunately, processed salmon sent to market are cleaned so thoroughly that finding a louse would be very rare, and, even if one was found on a filet, they are safe to eat, according to Green Matters. Though a parasite that feeds off mucus, blood and skin is unlikely to taste very good, humans have no reason to fear that a sea lice infection can spread from salmon to person.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, sea lice are a well-established hazard in the fish farming industry. While the damage dealt is generally harmless and nonlethal, there has been public outcry over poor management strategies in recent years.

Since sea lice can escape fish farms and harm wild fish, communities that rely on wild-caught fish have voiced concerns about the sustainability of fish farms. This is mainly because juvenile fish in these neighboring waterways are more likely to die, impacting future spawning generations of fish.

Many fishery managers treat their salmon with Slice, a lice treatment chemical. Still, some theorize that lice have developed a resistance to the chemical, making fish like cunner and lumpfish the perfect natural solution to a sea lice invasion.

Pingback: FishSens Magazine | How Fish Escape Aquaculture Facilities - FishSens Magazine