Plastic to the Core: Invasion of the World’s Oceans

Charles Moore: Sailing the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (Credit: Juan Pablo Calderón, CC 2.0)

Charles Moore: Sailing the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (Credit: Juan Pablo Calderón, CC 2.0)As videos of sea turtles choking on plastic straws and birds, seals, turtles, fish, and other aquatic life ensnared by plastic rings flood the internet, these happenstances are only a whisper of the magnitude of plastic pollution in the ocean. The reality is that plastic (micro or macro) contaminants can be found virtually everywhere in the ocean.

The world’s deepest ocean trench, the Mariana Trench, “extends nearly 10,975 meters (36,000 feet) down in a remote part of the Pacific Ocean,” according to National Geographic. However, the trench’s depth does not protect it from the same plastic pollution seen everywhere in the ocean. In fact, while the deepest piece of trash discovered in the trench was a plastic bag found at 10,975 meters, plastic waste is also common throughout the rest of the trench.

Much like how wildlife near the surface can become entangled by the debris, organisms within the trench are equally susceptible to harm. While it’s easy to assume that such a dark and deep environment would not have much life, the reality is entirely different. The Mariana Trench contains a diverse known species list and likely an even more extensive unknown species list.

The deepest part of the trench, the Challenger Deep, has only been visited by scientists a couple of times in history, the first of which was in 1960, according to National Geographic. The descent took five hours, and the divers, Jacques Piccard and Navy Lt. Don Walsh, only spent 20 minutes at the bottom, but they were shocked to find life at the bottom of the trench.

Prior to the dive, some marine biologists theorized that it would be impossible for life to survive at the bottom of the trench because of the extreme pressure (eight tons per square inch). And yet, the divers found a bundle of biodiversity at the bottom of our world. Nestled 7 miles below the surface, a host of diverse species are threatened by the same pollutants as their surface-welling counterparts.

More recently, unmanned deep-sea explorations have led to the discovery of more aquatic life in the Mariana Trench and, unfortunately, more plastic too. National Geographic reports that most of the plastic found throughout the ocean, about 89%, are single-use plastics.

Single-use plastics are any plastic item intended to be used once and then thrown away. Plastic straws, water bottles, and disposable utensils are all examples of single-use plastics and can be found scattered along the sea floor across the globe.

Deep-sea anemone Isactinernus observed in the abyss by the NOAA Okeanos Explorer mission in the Mariana Trench. (Credit: NOAA Okeanos Explorer, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

According to The Ocean Cleanup, “The Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) is the largest of the five offshore plastic accumulation zones in the world’s oceans. It is located halfway between Hawaii and California.”

Most of the 1.15 to 2.41 million tonnes of plastic that enter the ocean are less dense than the water itself, meaning that it will never sink and will remain on the water’s surface. This is a problem as the hordes of trash flowing from the rivers to the sea conglomerate in a few set places on the earth’s oceans due to circulating currents.

These plastics accumulate into islands of trash that will slowly but surely become dangerous microplastics that will disburse throughout the ocean. As the spread of plastic waste does not appear to be slowing, these floating garbage piles will only continue to grow in size as new plastics are sucked into one of the five gyres.

According to The Ocean Cleanup, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is roughly twice the size of Texas. It also weighs approximately 100,000 tonnes considering its more dense center and less dense exterior. The Ocean Cleanup conducted several massive surveys to analyze the size, quantity and components of the GPGP, and the results exceeded previous estimates.

How Plastic in the Ocean Impacts Human Health

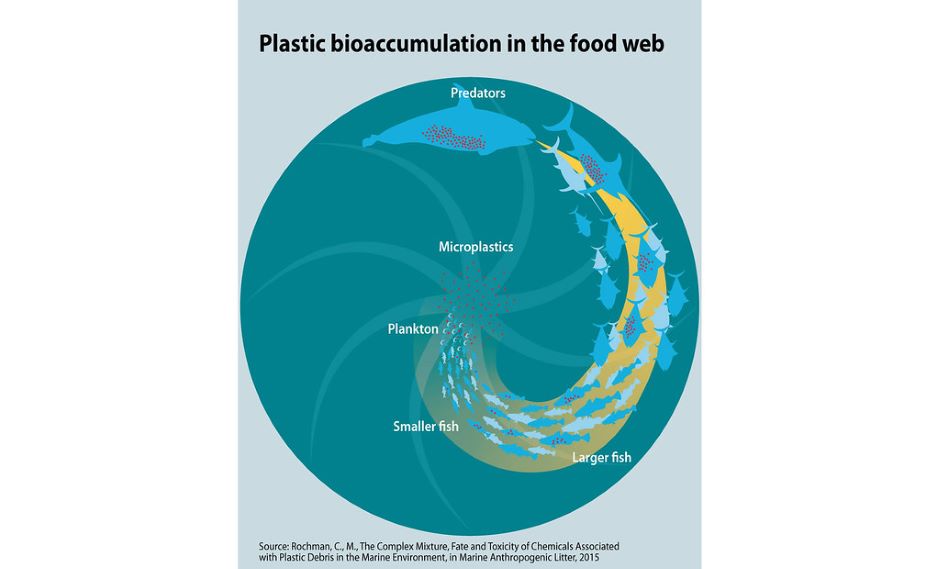

The main issue with the GPGP is that its existence will have long-lasting and far-reaching ramifications for the foreseeable future. Through a process called bioaccumulation, microplastics and the toxins they carry spread throughout ecosystems and up through the ecological chain. Smaller aquatic life digest plastics and are then eaten by larger fish, which are then eaten by humans.

The process causes illness and toxins to spread throughout the food chain and will only worsen as time goes on. A 2020 literature review revealed that 60% of fish contained microplastics, with the greatest concentrations being found in carnivores—a particularly concerning statistic considering that one of the most sought-after fish, the blue marlin, is a carnivore.

The invasion of plastic into the world’s oceans has become an environmental health concern. If plastic contamination levels continue at their current rate, the problem will only become larger.

Plastic bioaccumulation in the food web (Credit: GRIDArendal is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.)

What Can You Do to Reduce Plastic Waste?

With the planet’s future at stake, taking any steps within one’s ability can make a big difference. A plethora of Zero/Minimal-Waste guides can be found online and may provide more details and advanced guides toward a greener lifestyle. One of these guides is from the Environmental Protection Agency.

Most of the guidelines follow the same three words most students learn in primary school: Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle. The adage is so ingrained in our minds that it’s almost easy to ignore. However, the steps have proven to be effective and, when properly integrated with your daily routine, hardly an inconvenience.

Supporting legislation that prevents the expulsion of plastic waste from industrial sites can also be impactful in protecting the world’s oceans. Single-use plastics are a significant contributor to waste. Still, larger objects, or megaplastics (plastics larger than 50 cm), were the most significant contributors to mass in the GPGP, meaning pollution often goes beyond the individual’s direct control.

Conclusion

The future of the world’s oceans is difficult to conclude, but plastic debris has proven to be a scourge on marine and terrestrial life. Many marine organisms find themselves wrapped up in discarded fishing nets, ropes, fishing lines, or plastic containers, and the solution is something that most of the world has known since childhood.

Reduce use whenever possible, reuse old products by finding a new use or home for the items, and recycle retired goods into something that works for the individual—all of which can be done without sending anything to the landfill.

Featured Photo: Charles Moore: Sailing the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (Credit: Juan Pablo Calderón, CC 2.0)

Pingback: FishSens Magazine | Sacramento Chinook Salmon: Positive Population Trends - FishSens Magazine

Pingback: FishSens Magazine | Understanding the Ecological Impacts of PBDEs - FishSens Magazine

Pingback: Research Brief: Microplastic Pollution in Lake Phewa, Nepal - Lake Scientist

Pingback: Research Brief: Using Red Swamp Crayfish as Bioindicators of Microplastic Pollution - Lake Scientist